Structural untrustworthiness is not built from villains.

It’s built from fear, ambition, and obedience — woven into a system that rewards the wrong instincts and punishes the right ones.

Within such a structure, people don’t set out to destroy lives.

They drift into doing so, one rationalisation at a time.

🩸 The Anatomy of Structural Untrustworthiness

1. It feels like urgency and loyalty

At RBS’s Global Restructuring Group — the “slaughterhouse” — staff were told they were saving the bank and protecting the taxpayer.

Targets were framed as patriotism: “We must recover value; we owe it to the nation.”

That urgency became a moral narcotic.

Loyalty was mistaken for virtue.

Harm done in the bank’s name was reframed as necessity.

“We’re helping the bank survive,” they told themselves — even as they dismantled viable businesses.

The human cost disappeared under the fluorescent light of “performance.”

2. It looks like professionalism — but smells like fear

Every meeting, every email, carries a quiet tension: say too much and you’re out.

Compliance means self-preservation.

The vocabulary of conscience — “right,” “fair,” “just” — disappears, replaced by “policy,” “procedure,” “portfolio management.”

You feel trapped in a structure that rewards silence and punishes truth — yet you keep going, because leaving feels like losing your identity.

3. It tastes like success — for a while

Bonuses, promotions, overseas reward trips — the system feeds your ambition just enough to confuse compliance with achievement.

Your spreadsheets look good. Your conscience flickers.

You meet targets, but the applause sounds hollow.

Still, you can’t stop. The system has made your livelihood dependent on the harm you can’t yet face.

4. It feels rational — because empathy has been outsourced

When clients cry or plead, you tell yourself: “It’s not personal — it’s business.”

You call it “restructuring,” “de-risking,” “optimising capital.”

Deep down, you sense the lie — but you build psychological armour to survive it.

The slaughterhouse doesn’t smell of blood.

It smells of paperwork.

The harm is bureaucratic, not bloody. That’s how good people stay inside it.

5. It feels safe — because everyone else is doing it

Consensus becomes camouflage.

You stop trusting your own moral compass because the institution’s compass always points to “compliance.”

You see others rewarded for behaviour that once made you uneasy.

Soon, that unease fades.

Then, one day, it returns — as shame.

6. It ends in awakening — or in numbness

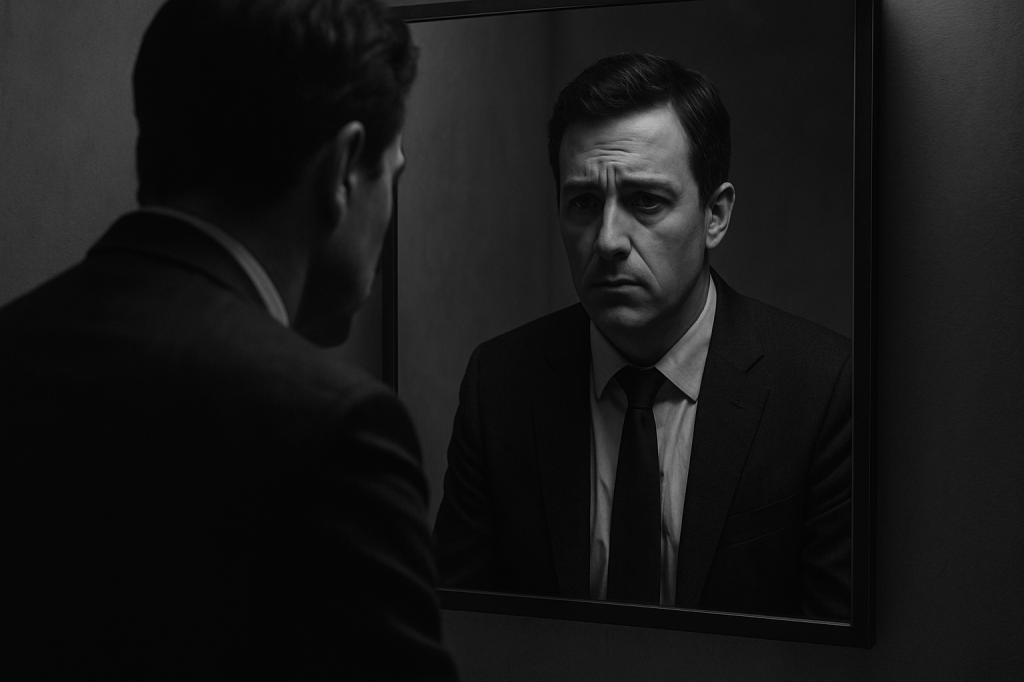

When the structure finally collapses, or you leave it behind, you look back and whisper:

“How could I have believed this was right?”

Because everyone around you did too.

Because the culture redefined rightness as obedience.

Because the hierarchy redefined loyalty as morality.

Because the structure absorbed your conscience like a sponge.

Is Where I Work Structurally Untrustworthy?

It’s easy to point to the RBS GRG scandal as an anomaly.

Harder is to ask whether the same moral architecture exists — quietly — where we stand today.

Perhaps not through visible asset-stripping, but through moral outsourcing, selective blindness, and systemic convenience.

Ask yourself, gently but truthfully:

Is it right to…

- Tap into client assets for fees, telling yourself it’s “value-added service,” even when the value flows mostly one way?

- Flog products and gather AUM under the banner of “advice,” believing that what enriches the firm must surely help the client?

- Ignore 80% of total wealth, human capital — mind, body, relationships, purpose — while meticulously managing financial capital?

- Plan the money before planning the life, because that’s what the compliance process demands?

- Treat the portfolio as the client instead of the person whose life depends on it?

- Accept hidden commissions, referral fees, or soft-dollar perks, because “everyone does it”?

- Exploit trust to sustain profit, even as families lose homes and hope — calling it “market correction” or “recovery”?

Or, in other corners of the system:

- As a Financial Ombudsman Service investigator, perhaps you dismissed a case because “the complainant wasn’t eligible,” “not within our remit”, “out of time”, knowing the fault was systemic and the rulebook was bent to protect the institution.

- As an FCA officer, maybe you closed one eye because “the regulator approved it,” or “it confilcted with the growth agenda,” and the alternative — exposing it — felt career-ending.

- As a Treasury or HMRC official, possibly you rationalised a loophole as “fiscal efficiency,” or “we must follow the rules as written, even when we know it’s not right, ” even when it drained the pockets of fraud victims.

- As an MP, maybe you accepted a lobbyist’s briefing without asking who funded it — telling yourself, “It’s just how Westminster works.”

- As a judge, perhaps you leaned too heavily on precedent shaped by power, the bank’s expert, and not justice.

- As a journalist, maybe you left out the crucial line because it might upset a sponsor — or close the door to future access.

The Common Refrain

“I was obeying orders.”

“Compliance signed it off.”

“The regulator approved it.”

“That’s just how the model works.”

“I’m providing for my family.”

“We’re creating jobs.”

“Clients benefit from what we sell.”

Language sanitises conscience.

The trader blames the model.

The regulator blames Parliament.

The adviser blames the system.

The journalist blames editorial.

The civil servant blames the minister.

The minister blames the market.

And no one — no one — owns the harm.

“If I hadn’t done it, someone else would.”

“I couldn’t change the system.”

The Tragedy

The tragedy is not that these people were evil,

but that the structure trained their goodness toward destructive ends.

They were taught to call it professionalism,

to measure morality by compliance,

to equate ethical silence with stability.

Until one day, the structure collapses — and someone whispers:

“How could I have believed this was right?”

The Invitation

Every professional in finance, regulation, law, politics, media, and oversight must hold up the slaughterhouse as the mirror of what bad looks like.

Not to condemn — but to awaken.

Because structural untrustworthiness does not begin with corruption.

It begins when good people stop asking questions.

🌍 From Untrustworthiness to Integrity

If structural untrustworthiness is the disease, then conscious design is the cure.

It begins when we stop seeing compliance as morality, and start restoring the human purpose behind every financial act.

It grows when advisers become planners again — not sellers of products, but stewards of people’s lives.

It matures when regulators, journalists, and civil servants remember that their true client is the public, not the institution.

At the Academy of Life Planning, we call this structural trustworthiness — the alignment of conscience, competence, and community.

It means planning the life before the money.

It means designing systems that serve human flourishing, not extract it.

It means measuring success not by growth, but by goodness.

Because integrity is not what happens when the cameras are on.

Integrity is what remains when the structure itself is just.

So let every professional — banker, planner, regulator, journalist, or judge — pause before the next policy, product, or decision and ask:

Is this structurally trustworthy?

Does it serve life, or does it serve the system?

That single question, asked often enough, could turn every slaughterhouse back into a sanctuary.