It was 2011.

I was Head of Investments at HSBC and Chair of the British Bancassurance Association’s Steering Group in the run-up to the Retail Distribution Review.

I remember sitting in those meetings, confused about why the Sales Director always accompanied me. He never said a word. At the time, I thought it was simply political theatre. Now I know: he was there to keep an eye on me — to ensure I didn’t get wind of the bank’s biggest internal secret.

They were preparing to exit Bancassurance.

No one told me, even though I was the most qualified investment professional in HSBC UK retail banking. They didn’t seek my advice. They didn’t ask what our pilots had proven. They relied on accountants and risk managers — people who looked at the world through the rear window of the back book — and declared that Bancassurance was “a zero-sum game.”

Their decision was simple:

“We can make more on lending. The Weighted Average Cost of Capital is too high on investments.”

That phrase — too high — has haunted me ever since.

Because it wasn’t true.

It wasn’t that Bancassurance couldn’t work.

It was that trust didn’t fit their business model.

The Project They Rejected

At the time, I had been leading what we called The Trusted Adviser Project.

It was revolutionary — not because of technology or product innovation, but because it placed human trust at the centre.

We trained advisers to plan the life before planning the money, creating a transparent, client-led model free from product bias.

The results were astonishing:

- Share of wallet rose from £1 in £8 to £8 in £8.

- Client conversion rates jumped from 1 in 4 to 4 in 4.

- Customer satisfaction soared.

- And regulatory compliance improved dramatically.

It was proof that a structurally trustworthy model could deliver both integrity and profitability. But it threatened the old order.

Instead of nurturing this model, the banks turned their backs on it.

Why Lending Won — and What It Cost

When the banks chose lending, they weren’t just shifting business lines. They were re-engineering capitalism.

Lending, unlike advice, could be securitised, sold, and recycled.

- Loans could be bundled into CDOs and moved off balance sheet.

- Recovery rights could be retained, turning default into profit.

- SME loans were classed as “commercial,” avoiding FCA oversight and FOS redress.

In short: lending offered a capital-light, risk-free illusion of profit.

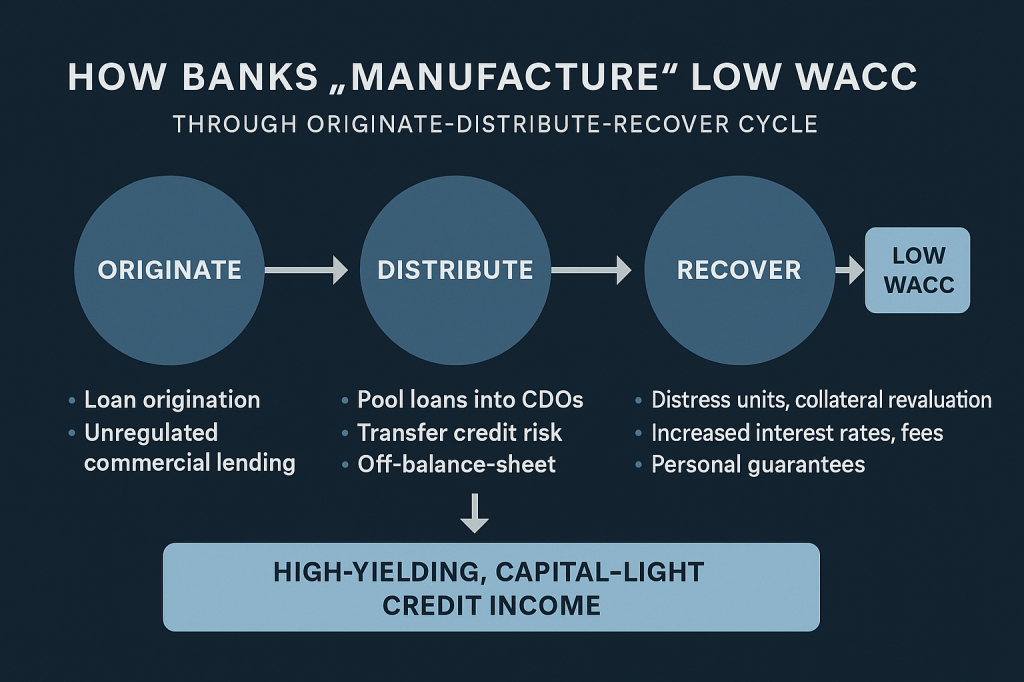

The banks had found a way to manufacture low WACC — not through genuine efficiency, but through structural exploitation.

And the victims?

Thousands of small business owners who lost everything when the recovery units came calling. Properties repossessed. Signatures forged. Personal guarantees fabricated. Lives destroyed.

All because a spreadsheet said lending was more “efficient” than trust.

The Road Not Taken

When I left HSBC in 2011, I left with unfinished work — the dream of a system where advisers serve clients, not balance sheets.

Since 2012, that dream has taken form as the Academy of Life Planning:

a global movement proving that trust delivers growth, not the other way around.

We teach planners to build transparent, client-first, product-free businesses — where success is measured in empowerment, not extraction.

Where financial planning begins with human capital, not financial capital.

A Reckoning for the Industry

Looking back, I see that 2011 was a fork in the road.

Banks could have chosen to reform and lead a new era of trust-based financial planning.

Instead, they chose to monetise distress and financialise life itself.

But that story isn’t over.

The Academy of Life Planning exists to finish what the Trusted Adviser Project began — to rebuild the profession around integrity, autonomy, and purpose.

Because when trust is the foundation, growth follows naturally.

And when it isn’t, even the most profitable business becomes a zero-sum game.

The Irony of It All

There’s a deep irony I can’t ignore.

The very people harmed by the banks’ decision to abandon trust and double down on lending — the entrepreneurs, small business owners, and families whose lives were dismantled by predatory recovery practices — are the same people I now serve through Get SAFE (Support After Financial Exploitation).

Back in 2011, those clients were the backbone of the local economy.

They weren’t gamblers or speculators — they were honest people who borrowed in good faith, trusting that their bank would act as a partner in their growth. Instead, when the tide turned, they found themselves trapped in a machine designed not for partnership, but for profit extraction.

- Loans were reclassified to trigger penalties.

- Interest rates were hiked without mercy.

- Properties and livelihoods were seized in the name of “risk management.”

- And all the while, the institutions responsible hid behind legal firewalls and unregulated loopholes.

Now, years later, those same victims come to me for help — not as a banker, but as an advocate, educator, and planner.

Through Get SAFE, we give them the tools to investigate wrongdoing, seek redress, and rebuild their lives.

Through the GAME Plan, we help them rediscover purpose, restore autonomy, and design a future not dictated by fear, but by freedom.

The system that broke them was engineered on the false promise that lending was safer, easier, and more profitable than trust.

But the truth is simple: when profit is prioritised over people, risk becomes inevitable — it just shifts downstream to the vulnerable.

Today, I see the full circle.

The clients who were once seen as “bad debt” are, in fact, the conscience of the financial system — and the living proof that a trust-based economy is not only possible but essential.

Get SAFE and the Academy of Life Planning now stand where the banks once stood — on the side of the people.

And this time, we are building a system that cannot be weaponised against them.

From Exclusion to Empowerment

When I walked out of the bank in 2011, I carried with me a deep sense of loss — not just for a career, but for a principle.

I believed that finance could be a force for good.

That trust and transparency could coexist with profitability.

That helping people live better lives was not naive — it was the true purpose of money.

At the time, I couldn’t see that the rejection of that vision was also its beginning.

The door that closed on me at HSBC opened a path toward something far greater — a movement to restore integrity, one life at a time.

The Academy of Life Planning was born from that moment of exclusion — to prove that structurally trustworthy models don’t just work; they transform lives.

And Get SAFE was born from the suffering that followed — to help those betrayed by the extraction model find justice, healing, and a new beginning.

Together, they form two halves of the same whole:

- One prevents exploitation before it happens.

- The other restores those who have been exploited.

Both are grounded in the same principle I learned long ago — that trust precedes trade, and that without structural trustworthiness, no system, however sophisticated, can stand the test of time.

So the irony has become redemption.

The clients once harmed by a system built on mistrust are now the very reason we are rebuilding it.

Their recovery is our proof of concept.

Their courage is our curriculum.

And their stories light the way toward an economy that finally puts people before profit.

Join us at the Academy of Life Planning.

Let’s raise capability and integrity — together.

Because only when products and services are structurally trustworthy can consumers truly be free.

Get SAFE Exists to Support After Financial Exploitation

Get SAFE (Support After Financial Exploitation) is building a national lifeline for victims — providing free emotional recovery, life-planning, and justice support through our:

- Fellowship: peer-to-peer recovery and community.

- Witnessing Service: trauma-informed advocacy for those seeking redress.

- Citizen Investigator Training: empowering survivors to uncover truth and pursue justice.

Our Goal: Raise £20,000 to Rebuild Lives

Your contribution will help us:

Register Get SAFE as a charity (CIO)

Build our website, CRM, and outreach platform

Fund our first year of free recovery and justice programmes

Every £50 Changes a Life

Each £50 donation funds a bursary for one survivor — giving them access to the tools, training, and community that restore confidence, purpose, and hope.

This Isn’t Just a Fundraiser — It’s a Movement

We’re reclaiming fairness and rebuilding trust, one life at a time.

Support the Crowdfunder today

Be part of the movement to rebuild lives and restore justice.

Additional Reading: Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

In 2011, low interest rates should have made lending margins unattractive compared to fee-based business like bancassurance. Yet the banks concluded the opposite — that lending, not advice or insurance, would deliver the superior risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) and therefore lower their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

Here’s how and why that worked:

1. Regulatory Arbitrage and Capital Efficiency

After the 2008 crisis, Basel III capital rules made it far more expensive to hold “risky” assets on balance sheet.

- Bancassurance commissions were seen as volatile and reputation-sensitive.

- Loans, however, could be structured, securitised, and off-loaded — allowing banks to originate and distribute rather than hold the risk.

That meant they could generate lending income without tying up equity capital, effectively reducing WACC.

2. Securitisation Returns Without the Risk

As you noted, banks could pool loans into Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) or similar instruments and sell them to investors.

- They booked upfront gains and retained servicing or recovery rights, giving them a “second bite” at profits if a borrower defaulted.

- The capital markets bore the credit risk, while banks earned fee and recovery income with little capital charge.

This “capital-light” model made lending appear extraordinarily profitable on a WACC basis.

3. Regulatory Exemptions for Commercial Lending

Most commercial and SME lending was unregulated by the FCA and outside the FOS remit.

- That meant minimal compliance cost and litigation risk — a structural trust discount baked into the model.

- Recovery units like Lloyds’ Bristol Business Support Unit (BSU) operated in that grey zone, extracting profits from distressed borrowers with impunity.

The lack of consumer protection effectively raised expected returns per unit of regulatory risk.

4. Accounting Flexibility and “Zombie” Interest Income

Under IFRS accounting, banks could accrue interest income on loans even when they were distressed, until formally written off.

That allowed them to book profits now, defer losses later — a powerful WACC illusion.

Distress-unit recoveries, inflated valuations, and property mark-ups kept “profit per pound of capital” high, even as underlying risk rose.

5. Ultra-Low Funding Costs

Although interest rates were near zero, the cost of bank funding was even lower than the policy rate, due to:

- Cheap central-bank liquidity (QE, Funding for Lending Scheme, TLTROs)

- Deposit inflows seeking safety

So the net interest margin (spread between 0 % funding and 3–7 % SME lending) remained wide enough to generate strong nominal returns, even at low rates.

6. Exit from Bancassurance = Reputational and Regulatory Risk Control

Post-RDR (Retail Distribution Review), bancassurance was viewed as:

- Labour-intensive

- Commission-banned (so fee-only)

- High conduct-risk exposure (mis-selling legacy)

By contrast, commercial lending promised asset-based, institution-to-institution control with minimal FCA exposure. The WACC equation favoured predictable, capital-engineered credit income over uncertain advice-based margins.

7. Structural Incentive to Extract Value from Distress

Once loans were “warehoused” in recovery units:

- Banks could revalue collateral and book gains.

- Distressed interest rates and penalty fees were treated as new income streams.

- Defaults often triggered personal guarantees, converting limited-company debt into personal liability.

All this inflated the Return on Equity (ROE) denominator in their internal capital models — and therefore made the lending business look vastly more profitable on paper.

In short

In 2011, lending became the perfect alchemy: risk-free in regulation, capital-light in structure, and high-yield in distress.

That’s why the WACC story flipped.

Bancassurance tied up human capital and compliance cost for diminishing returns; lending could be securitised, off-balance-sheeted, and “harvested” through recovery.

It wasn’t that lending truly lowered WACC — it’s that banks engineered the appearance of low WACC by externalising risk and internalising recovery profit.

Why Untrustworthy Systems Depress GDP (The Devaluation Penalty)

When markets lose trust in a financial or institutional system, they price in higher perceived risk. This risk premium acts as a tax on productivity and growth, operating through four reinforcing channels:1. Higher Cost of Capital → Less Investment

Investors demand higher returns to compensate for governance risk, opacity, or corruption.

That raises borrowing costs for businesses and government alike.

As capital becomes more expensive, productive investment slows, innovation declines, and GDP growth weakens.

📉 Empirical evidence: The World Bank finds that a one-point fall in institutional trust correlates with roughly a 0.6–1% decline in GDP per capita growth (Kaufmann & Kraay, “Governance Indicators,” 2020).2. Lower Productivity → Weaker Output

Distrust increases monitoring, auditing, and compliance costs.

Firms duplicate oversight functions instead of focusing on innovation.

Labour productivity falls as energy shifts from creation to control.

📉 High-trust economies like the Nordics consistently outperform on output per worker — their “trust premium” is worth several percentage points of GDP.3. Reduced Consumer and Business Confidence → Lower Demand

When citizens don’t trust financial institutions, they save defensively, hoard liquidity, and spend less.

Businesses delay expansion amid policy uncertainty.

Aggregate demand shrinks — directly cutting GDP.

📉 OECD trust metrics show consumer confidence tracks closely with perceived institutional integrity.4. Talent and Capital Flight → Structural Underperformance

High-trust environments attract investment and skilled labour; low-trust ones repel them.

Over time, brain drain and capital flight reduce national capacity, productivity, and fiscal receipts.

📉 IMF research links governance quality to sustained FDI inflows and long-term GDP resilience.In short:

That’s why our framing — “The Trust Discount depresses GDP; the Trust Premium lifts it” — isn’t rhetorical. It’s macro-economic fact.