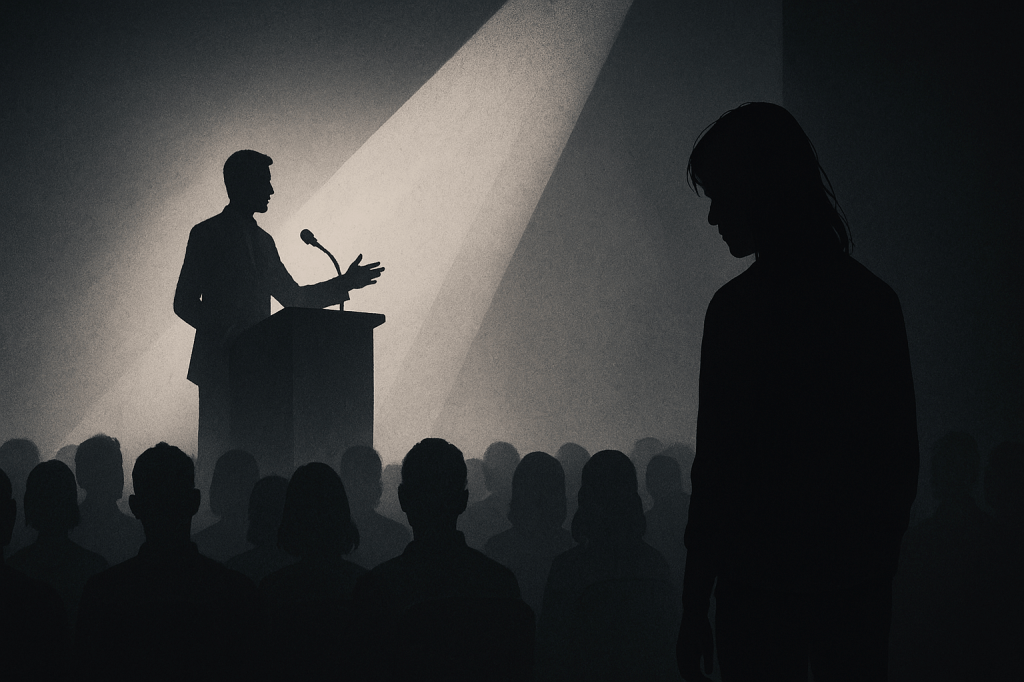

The recent debate surrounding the BBC’s platforming of convicted fraudster Alex Wood has sparked important—and at times uncomfortable—questions about who gets to lead the conversation on fraud prevention.

Let me be clear: I believe in redemption. People can change. But redemption is not the same as rebranding.

When we place those who once caused harm at the centre of public education without equal representation of the harmed, we risk repeating the imbalance that enabled abuse in the first place.

🧩 This is not personal. It is structural.

My blog, Redemption or Reputation Laundering?, wasn’t an attack on an individual—it was a critique of a growing trend:

- Former perpetrators being elevated as experts (see below),

- Victims being sidelined or silenced,

- And trust-based institutions rushing to platform compelling stories, without doing the deeper work of ethical framing.

The media loves a “conversion narrative.”

The fraudster-turned-saviour trope makes for great headlines. But let’s not confuse storytelling with integrity. If we fail to interrogate these narratives, we risk enabling “fraud-washing”—where past crimes become credentials, and remorse becomes a marketing tool.

🔍 Why this matters:

- Restitution is rarely addressed. Legal compliance is not moral atonement.

- Victim voices are missing. Where is their grief, trauma, or recovery in the coverage?

- Trust is a currency. If public broadcasters and government agencies invest trust in the wrong voices, they risk losing it with the public.

I’ve been contacted by whistleblowers, survivors, and professionals from across the fraud prevention field who share these concerns. Many of them are too afraid to speak out. Some have been harmed before. Others are still picking up the pieces.

Their consensus is simple: platforms must be earned—not granted on the basis of past harm.

✊ What I’m calling for:

- Victim-first framing in all public conversations on fraud.

- Full transparency around financial gain, legal restitution, and institutional due diligence.

- Ethical governance from media, regulators, and advisory bodies.

We can learn from reformed individuals—but only when that learning is grounded in humility, guided by survivor wisdom, and free from personal brand-building.

This isn’t about silencing anyone. It’s about ensuring we centre the right voices when trust and justice are on the line.

Let’s move forward together—but with eyes open, and conscience intact.

What Happened Next — And Why It Matters

After I published this article and shared it on LinkedIn, I was met with a flurry of personal attacks from one of the individuals mentioned—someone who presents publicly as an advocate for victims and co-host of a high-profile media programme on fraud. Rather than respond to the article’s substantive points, they launched into repeated, sarcastic, and increasingly hostile comments under the post.

The focus quickly shifted from professional debate to personal disparagement: questioning credentials, levelling false accusations, demanding private information, issuing legal threats, and even suggesting a physical confrontation. Despite my attempts to de-escalate, keep the conversation constructive, and ultimately withdraw, the attacks continued.

This behaviour speaks volumes—not about me, but about a concerning trend. In a space where credibility, humility, and accountability should be the baseline for any advocate working with or speaking for victims of financial harm, public intimidation has no place.

It also reinforces the very point of the article: we must hold all advocates—especially those with media platforms—to the same standards of transparency, responsibility, and respect that we ask of the institutions we critique. When someone claiming to support victims silences or slanders those who ask reasonable questions, it becomes a form of re-victimisation in itself.

Let this be a reminder: integrity is not just about what someone did in the past—it’s how they behave now, especially when challenged.

Glamourising fraudsters hurts victims of fraud, and society.

“Glamourizing fraudsters hurts victims of fraud, and society” by Martina Dove, published on the Fortra (Tripwire) blog.

1. Society glamorises fraudsters at victims’ expense.

There’s a cultural fascination with fraudsters, especially in media, where charismatic con artists are often depicted as clever anti-heroes. This narrative often ignores or diminishes the suffering of their victims.

2. Victim-blaming is widespread and harmful.

Victims of fraud are often blamed for being “naïve” or “greedy.” This stigma adds emotional harm and discourages them from seeking help. Victims already face trauma, loss, shame, and isolation, and public discourse often amplifies these effects.

3. Fraudsters manipulate empathy and spend money to maintain power.

Offenders may treat victims generously at first to gain trust. But this spending is strategic, not genuine generosity—it is part of their manipulation and control.

4. Justice is rare.

Very few fraudsters face prosecution, and victims seldom see justice or compensation. Authorities often deem fraud as a “civil matter,” and systemic issues prevent effective redress. Only about 1 in 10 reported frauds are prosecuted in the UK.

5. Society’s treatment of victims defines its values.

The article argues that how we treat fraud victims reflects the health of our society. Dismissing fraud as victim error rather than criminal exploitation normalises abuse. Elevating fraudsters as clever and “hustling” reinforces toxic, extractive systems.

Former perpetrators being elevated as experts

Below is a short list of evidence and citations demonstrating the trend of former perpetrators being elevated as experts, particularly in fraud and cybercrime spaces. These examples span media, law enforcement partnerships, and corporate training.

🔍 1. Frank Abagnale – “Catch Me If You Can”

Background: Former con artist and forger, subject of the film Catch Me If You Can.

Post-crime role: Became a lecturer at the FBI Academy and has advised numerous organisations on fraud prevention.

Controversy: Much of Abagnale’s story has been challenged as exaggerated or false.

Reference: Logan, A. (2021). The Greatest Hoax on Earth: Catching Truth, While We Can.

The Guardian Article on Doubts. See Wikipedia.

🔍 2. Tony Sales – UK Retail Fraudster Turned Consultant

Background: Once dubbed “Britain’s Greatest Fraudster”; stole over £30m.

Post-crime role: Co-founded We Fight Fraud, advising corporates, banks, and police forces.

Public Platforming: Featured in media and major fraud events as a keynote speaker.

Reference: BBC News (2020). Fraudster turned fraud-buster: Tony Sales fights back.

BBC Article/ See YouTube.

🔍 3. Michael Fraser – Ex-Burglar Turned Security Expert

Background: Reformed burglar who later presented Beat the Burglar on the BBC.

Post-crime role: Became a household name advising the public and homeowners on how to prevent break-ins.

Reference: The Guardian (2005). From burglar to TV presenter.

The Guardian

🔍 4. Alex Wood – BBC ‘Scam Secrets’ Co-host (Your Current Case)

Background: Convicted fraudster who committed APP scams estimated to total £50 million.

Post-crime role: Now co-hosts Scam Secrets on BBC Radio 4 and runs ‘Reform Courses’.

Concerns Raised: Victim voices absent from mainstream coverage; no evident third-party restitution.

Reference: The Sunday Times (2025). “I stole £1.2m in a 40-minute call — then blew it all in Harrods.”

🔍 5. Reformed Hackers in Cybersecurity

Example: Kevin Mitnick (US hacker turned security consultant).

Post-crime role: Became a leading “white-hat” hacker and was hired by security firms, including KnowBe4.

Reference: Wired (2023). Kevin Mitnick, hacker turned hero, dies aged 59.

Wired Obituary. See Wikipedia.

Kevin Mitnick’s case exemplifies the broader pattern where former perpetrators become prominent subject-matter experts—often without transparent evidence of restitution or meaningful victim involvement. Their notoriety becomes a commercial asset, yet the framing rarely includes survivors’ voices or accountability beyond legal compliance.

🧩 Summary of the Pattern

These individuals are often elevated to expert status based on notoriety, not necessarily evidence of remorse, restitution, or victim consultation.

Their stories are widely commercialised, sometimes at the expense of victims’ dignity or public trust.

Media institutions and conference organisers have increasingly used them as “insiders” who offer exclusive insight—without sufficiently vetting ethical concerns.

What This Illustrates

- Rehabilitation narratives are widely promoted, but rarely linked to tangible victim restitution or third-party verification.

- Media and corporate platforms often equate infamy with expertise, sidelining ethical scrutiny and failing to amplify survivor voices.

- These individuals occupy expert roles without necessarily participating in meaningful restorative justice or supporting victim-led organisations.

- Their stories are widely commercialised, sometimes at the expense of victims’ dignity or public trust.

Author: Steve Conley

Founder, Academy of Life Planning & Co-Founder of Asset Recovery Network (UK) Limited, Member of the Advisory Group of the Transparency Task Force.

#FraudReform #Redemption #Restitution #VictimVoices #EthicalLeadership #BBC #ScamSecrets #FraudAwareness #AoLP #StructuralJustice #FraudWashing #HolisticAccountability

If you are a fraud survivor or work in financial justice and want to share your views on this issue, feel free to get in touch.

http://www.aolp.co.uk | @RatBaggery | steve.conley@aolp.co.uk

About Get SAFE

Get SAFE (Support After Financial Exploitation) was born from a simple truth: too many victims of financial abuse are left to suffer in silence.

We exist for people like Ian—for the ones who did everything right, only to be failed by the systems they trusted. We know that behind every vanished pension, every ignored complaint, and every stonewalled letter is a person—frightened, exhausted, and too often alone.

Get SAFE offers more than sympathy. We offer structure, support, and solidarity.

We provide a voice where there’s been silence, and clarity where there’s been confusion.

We stand beside those who have been exploited, not just to help them recover—but to help them reclaim their story and rebuild their future.

Because financial justice is not a luxury.

It’s a human right.

If you or someone you know has been affected by financial exploitation, we are here.

You are not alone.

Learn more at: Get SAFE (Support After Financial Exploitation).

One thought on “Redemption, Restitution, and Responsibility: Why This Debate Matters”